by Mohammad Kareem

This August marks the centenary of the Treaty of Sèvres, signed between the Allied powers and the Ottoman Empire in 1920. The Treaty was never ratified, being replaced by the Lausanne Agreement in 1923. Historians have considered it stillborn – ‘the world of illusions’ in Churchill’s words. For Kurds and Turks, however, it lives on in memory, if from different perspectives. For Kurds, the Treaty was the first ever international recognition for their political rights, envisaged in Articles 62, 63 and 64. For Turks, however, it represented an attempt at the elimination of the empire and the partition of Turkey by foreign powers.

For over a century, the Kurdish quest for statehood, and the Kurdish question – described by Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov as a ‘bomb’ for the entire region – has remained a major challenge for Middle Eastern stability and security. The root causes date back, at least, to the dismembering of the Ottoman Empire with the purpose of establishing a new nation-state system, which excluded any Kurdish entity. Since the post-Ottoman order failed to create a stable and peaceful region, it was famously termed as a ‘peace to end all peace’ by David Fromkin, sowing the seeds of subsequent conflicts in the region. Essentially, Anglo-French diplomacy was at the heart of the Middle East’s instability and tensions in the immediate post-war period, with their strategic and economic disputes over Syria, Mosul, Kurdistan and Turkey being the main obstacles to achieving a reasonable political arrangement for its inhabitants. The two powers’ imperial interests dominated the peace conference and ran contrary to applying the Wilsonian concept of self-determination in the Middle East. Kurdistan’s future was fundamentally affected by this, preventing any settlement of the Kurdish question in the post-war period, and leading to the first systematic division of Ottoman Kurdistan between Turkey, Iraq and Syria.

The prospect of independence for Kurdistan had been much debated among British policymakers in which different, conflicting proposals and views were presented –whether a future Kurdistan should be independent, a federation or a single autonomous state, or carved up between the other new states. British perceptions of the Kurdish question were significantly influenced by a divergence of strategies and agendas, mainly reflected in two schools of thought, emanating from the India Office and the Foreign Office. These competing trends continued to influence British Middle Eastern policy for some time. In 1915, during the debate concerning the future of the Ottoman territories, the India Office’s view was to support the settlement of the Kurdish Question. Arthur Hirtzel, Political Secretary of the India Office, stated that without settling this question, the region would not witness peace and stability. Hirtzel reasoned that the establishment of an independent Kurdistan would be in British interests, as had been the case with the creation of Nepal.

However, under the influence of Mark Sykes the idea was rejected, and a resolution for the Kurdish question was absent in the Sykes-Picot agreement with France and Russia, which instead divided Kurdistan among new spheres of imperial influence. At the end of the war, however, the Sykes-Picot agreement faced strong criticism within the British establishment, where it was considered outdated and inconsistent with new developments, including Wilson’s Fourteen Points and the withdrawal of Russian participation following the Bolshevik revolution.

For the post-Ottoman settlement in the Middle East, various proposals and correspondence were submitted to the British cabinet, reflecting two principal competing visions of the political map in the region. The first was based on ethnic-sectarian and geographic realities, the second on strategic and economic imperial demands. Advocating for the former, Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour stated that any lasting peace must be based on the desires of the people and historical and geographical facts, not on the prospective financial and political gain of the major powers.

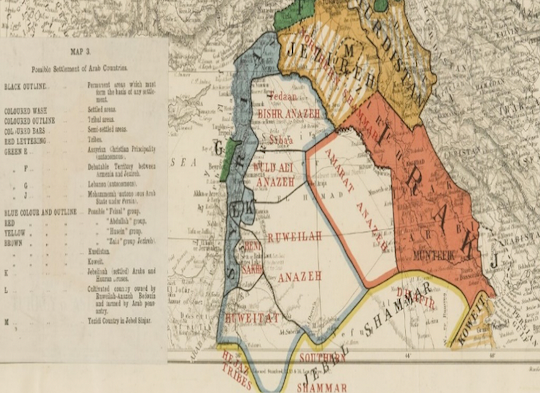

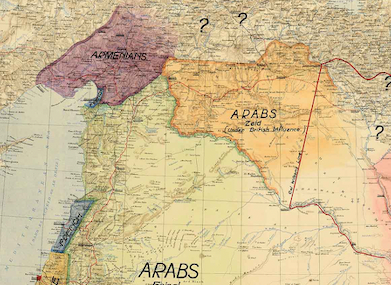

Thus, in the immediate post-war period, Kurdistan had appeared in certain proposed maps that reflected the first category.

Figure 1: India Office Records and Private Papers. Source: British Library, Mss Eur F112/276, f 102-103

Figure 2: India Office Records and Private Papers. Source: British Library, Mss Eur F112/276, f 102-103

T.E. Lawrence’s recently discovered map can be seen as a prominent example in this respect. He submitted it to the Eastern Committee in 1918, proposing a political map of the Middle East divided along ethno-sectarian lines, to include a Kurdish state in Southern Kurdistan. However, the idea was rejected. Although Lawrence was seen as pro-Arab amongst British officials, he was against the incorporation of Southern Kurdistan within the new Arab state of Iraq, established in 1921 under the King Faisal.

Figure 3: TE Lawrence’s Mid-East map on show, 11 October 2005. Source: BBC News

At the beginning of the Paris peace conference, Mark Sykes, now changing his mind regarding the Kurdish question, suggested the creation of an independent Kurdish state to include Mosul, but this was rejected by the French Foreign minister. Kurdish nationalists led by Sherif Pasha pushed for the recognition of the Kurdish Question on a par with the demands of the Arabs and Armenians, but it was omitted from the Paris peace conference’s agenda. However, the provision for Kurdish independence was first envisaged in the Treaty of Sèvres, but subsequently rejected by Turkish nationalists. Soon after the treaty’s signing, the Allied powers realised that it was impractical and needed to be revised, especially considering Ankara’s position concerning the Armenian and Kurdistan questions.

As far as the British Empire was concerned, the picture was more complicated, since London did not have a coherent Middle Eastern policy but remained split between the interdepartmental rivalry. As such, in December 1920, the Middle East Department was established by the new Colonial Office’s Secretary, Winston Churchill. Hence, early in 1921 Britain was ready to redesign its plans for the Middle East. On the international level the Foreign Office was busy with the London Conference in order to reach a political solution with the other Allied powers regarding peace with Turkey. On the other hand, the Colonial Office prepared for the Middle East conference in Cairo, geared towards determining British policy in the Mandate areas under the new formed Middle East department.

In the context, the establishment of a Kurdish buffer state between the Arabs and Turks became essential to Churchill’s Middle Eastern strategy. This idea however, faced opposition from British officials in Baghdad on strategic and economic grounds. In January 1921 at the request of Churchill, Major Young drafted a counterargument to Percy Cox’s reports about the future of Mesopotamia and Kurdistan. Young examined the political position of Kurdistan in the light of the revision of the Treaty of Sèvres and the Mesopotamian mandate, emphasising that the formation of a Kurdish entity as a ‘buffer state’ would serve as the best way to deal with potential external threats from Kemalists and Bolsheviks. Clearly, Young’s views had a considerable influence on Churchill and became the basis of the Cairo Conference. In June 1921, Churchill stated that Kurdistan was to have ‘Home Rule’ (as with Transjordan under Abdullah bin Hussain), with Sir Percy Cox in the same position in regard to it as the Higher Commissioner in South Africa is to Rhodesia. This was never achieved, with the plan instead subjugated to Anglo-Turkish relations after the rise of the Kemalist movement, with whom the British signed a new agreement in 1923 at Lausanne.

From this point on, the unmaking of an independent Kurdistan was shown to be one of the worst mistakes of the post-Ottoman international system, exacting a dreadful human cost in the countries destabilised by the post-WW1 order. The settlement of the Kurdish question could instead have been a major contribution to the Middle East’s peace and stability.

Mohammad Kareem is an independent researcher based in the UK. He received a PhD in Middle East Politics from the University of Exeter in 2018. His primary interests include colonialism, nationalism, and oil in the Middle East with a primary focus on Iraq and the Kurdish question.