by Dr. Gary K. Busch

'' There is a major battle going on for control of Syria’s oil and gas industry among the U.S., Russia, Iran and Turkey. The roots of the Syrian Civil War can be traced to conflicts over the control of Syria’s energy. Resolution of that conflict will depend heavily on resolving disputes over Syrian oil and gas, while ensuring an adequate supply of water in a continuously dehydrating climate''.

The roots of the Syrian Civil War can be traced to the conflicts over control of Syria’s energy supplies. Achieving a final conclusion to that war will also depend heavily on concluding arrangements for the distribution of Syrian oil and gas, onshore and offshore, and ensuring adequate supplies of water in a continuously dehydrating climate.

Syria has had many problems in its history, as well as opportunities, most of which have come from its location as an Arab country with broad access to the Mediterranean Sea. Iraq, Iran and Jordan all have access to the Mediterranean through Syria.

Syrian Oil & Gas

Syria’s oil reserves are small by Arab standards, yet the oil and gas sector is a crucial contributor to Syria’s government revenue and foreign exchange earnings.

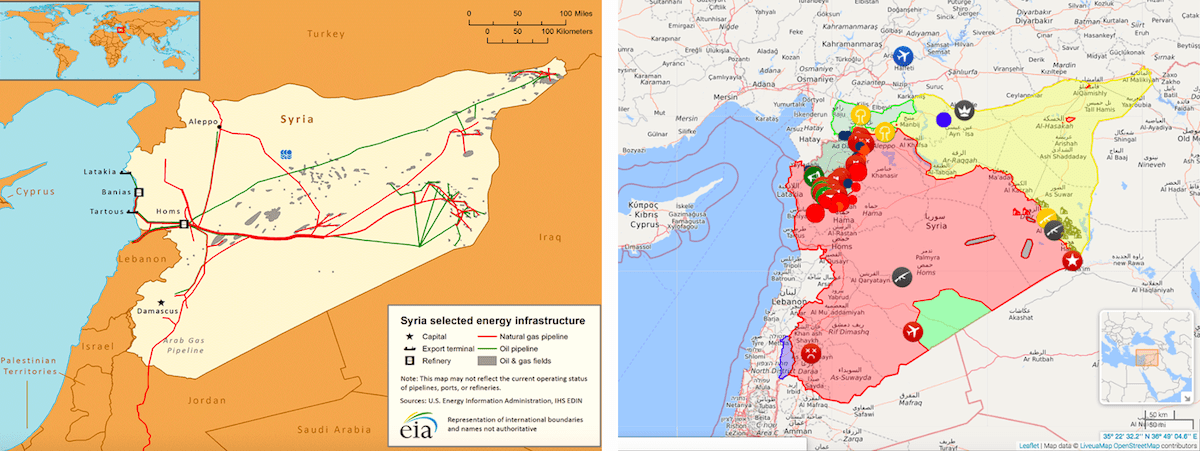

In 2010, the energy sector contributed about 35% of export earnings and 20% of government revenue. The Oil & Gas Journal estimated Syria’s oil reserves at 2.5 billion barrels, as of January 1, 2015. These are located mostly in the east and northeast. Natural gas reserves are estimated at 241 billion cubic meters, located primarily in central Syria. Most of Syria’s crude oil is heavy (low gravity) and sour (high sulphur content), which requires a specific configuration of refineries to process. This places its oil at the lower end of the price range.

Syria’s oil sector has been in a state of disarray since 2011. Production and exports of crude oil have fallen to nearly zero, and the country is facing supply shortages of refined products. The impact of this lack of supply is magnified by the effects of the sanctions placed on Syrian oil by the U.S. and the European Community.

As a response to the Syrian government’s support of international terrorism and violations against democratic and human rights in the country, sanctions were imposed by the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), the British (HM) Treasury, the European Union, the United Nations, and several other regulatory entities, one of the most comprehensive ever implemented. Currently imposed sanctions include trade restrictions, travel bans and asset freezes on certain Syrian officials, as well as a ban on Syrian investment by U.S. persons.

[SYRIA ENERGY (U.S. ENERGY INFORMATION) AND WWW.LIVEUAMAP .

[SYRIA ENERGY (U.S. ENERGY INFORMATION) AND WWW.LIVEUAMAP .

Syria’s domestic production of oil this year reached only 24,000 barrels a day, about 20-25 percent of the country’s total needs. This is down from about 350,000 barrels a day before the civil war. The government’s need for subsidized fuel was being met by Iran, which also offered vital military support to the regime of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad. This presumably ended by late 2018, as a result of the pressure of U.S. sanctions.

The U.S. Treasury also issued a global advisory warning of sanctions for illicit oil shipments, naming specific vessels, while pressuring insurance companies. At least one tanker with Iranian oil headed to Syria remained docked outside the Suez Canal since December 2018, according to TankerTrackers.com, yet recent indications are that Iranian shipments have resumed.

In early 2011, there were about two dozen international energy companies operating in Syria. Chinese, Indian, and Russian companies were particularly active, along with some European minor oil companies. The major interest in Syria’s energy industry was in exploration of its offshore acreage which abuts a rich treasure of Israeli gas fields. These finds indicated that there might also be subsea gas fields in both Lebanon and Syria.

A Syrian oil pipeline

Syria first became important for the delivery of crude oil from the rich Kurdish fields in Iraq when oil companies decided to create pipelines to the sea through Syria. For centuries Syria had been controlled by the Ottoman Turks, until, after the First World War, it was given to France to manage under the League of Nations Mandate. Syria only got its independence after the Second World War, but, in reality, it continued to be dominated by external forces.

In 1935, the British, who ran the Iraqi oil industry at that time, built the Mosul-Haifa pipeline. It ran from the oil fields in Kirkuk, northern Iraq, through Jordan to Haifa (then under the British Mandate of Palestine). At about 942 kilometres (585 mi), it took about 10 days for crude oil to travel the full length of the line. The oil was then distilled in Haifa refineries, stored in tanks, and then put in tankers for shipment to Europe. It provided most of the fuel needs of the British and American forces during the Second World War and was a key target for the Axis forces.

The pipeline, however, had been beset by waves of protests from the Palestinian Arabs, especially during the Arab Uprising of 1936-1940 led by Sheikh Izz ad-Din al-Qassam, and later the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem. The Palestinians fought against the British and the French colonial forces in Lebanon and Syria, as well as the Jewish settlers who had been allowed into Palestine by the British under terms of the Balfour Declaration. Al-Qassam was eventually captured and executed by the British, while the Grand Mufti allied himself with the Axis forces during the Second World War, with the Nazis and Vichy French determined to cut off oil supplies to the Allies.

Arab irregulars consistently attacked the Mosul-Haifa pipeline, and were later supported by a team of Abwehr specialists who advised the Grand Mufti about sabotaging the oil stream. These attacks on the pipeline made it clear to the oil industry that it would be difficult to protect the Mosul-Haifa pipeline in the face of a sustained Arab uprising as well as enduring the waves of strikes and go-slows of the organised workers in their territories.

And so began the planning of the Trans-Arabian Pipeline (the ‘Tapline’), an oil pipeline that would run from Saudi Arabia through Syria.

After the unsuccessful Arab-Israeli War in 1948, Syria maintained a fragile parliamentary democracy, but its political leadership was fired with the fury of Arab nationalism and frustrated by the signing of the peace treaty with the victorious Israeli state. The West was worried about the rise of a sustained hostility in the region and feared the rebuilding of a Soviet-supported Arab bloc which would threaten the multinational oil companies and Saudi Arabia’s export capacity.

To “fix” this problem, the CIA and the American Embassy in Damascus actively promoted a coup d’état.

In April 1949, the Army’s Chief of Staff, Husni al-Zaim seized power, jailing many of his opponents. Al-Zaim, who was in favour of a secular state, ordered the end of veiling of women and gave women the franchise. He also forced businessmen to pay taxes they owed. Most importantly, he signed a number of long-term deals with multinational oil companies to participate in the creation of the Tapline pipeline, which the previous government of Syria had refused to sign.

The construction of the pipeline had actually begun while the British Mandate of Palestine was still operative in 1947. It was designed and managed by the American company Bechtel. Originally the Tapline was intended to terminate in Haifa. However, due to the establishment of the state of Israel, an alternative route through Syria (Golan Heights) and Lebanon was selected with an export terminal in Sidon.

The Tribal Factor

The history of Syria’s energy sector cannot be fully understood without consideration of Syria’s tribal history. One of the most fundamental forces in Syrian political life, and the key to understanding the kaleidoscope of political interactions and coalescences, derives from the fact that Syria is divided into competing clans and tribes combined with regional identities.

Between 60 and 70 per cent of the Syrian population belongs to a clan or tribe. These tribal and clan relationships are not stable or fixed alliances. There are shifting loyalties and social changes which often cause strife among tribes and clans as well as within tribes as kin and outsiders seek dominance. These conflicts allow non-tribal entities to agree to alliances with and among the tribes and clans.

One result of the catastrophic transformation of Syria since the inception of its current civil war has been the reduction of the control of the tribes and clans by their traditional chiefs. These changes have allowed the tribes to ally themselves with the Syrian Government, the Syrian rebels, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), and ISIS (‘Daesh’), often on a fluid basis. As the conflict in Syria spread different tribes became identified with one or more of these combatants.

Until the fall of Raqqa and the defeat of ISIS there was grudging support of ISIS by the local tribes. However, as the Kurdish forces, the People’s Protection Units (YPG), began to succeed and expand their control of Northeast Syria, the tribes and clans began to participate with the Kurds in forming the Syrian Democratic Federation.

The successes of the SDF forces (aligned with U.S military advisors) and NATO aircraft in driving out the last vestiges of ISIS occupied territory, left the oil-rich centre of ‘Deir Ez-Zor in the hands of the SDF and their tribal supporters and presented an opportunity for clans of other ethnicities and religions, such as Kurdish, Turkmen, Alawite, Druze and Christian clans, to participate more fully in local politics.

Unfortunately for Turkey, the subsequent military successes of the SDF forces have left the Turks largely out of the equation and diluted the ties between the Syrian tribes and the Al Nusra Front in the oil-rich region. The efforts by the Turks to threaten the array of forces in Eastern Syria caused a major rift with the Syrian tribes; especially when they used tribal fighters in their efforts.

Getting the various tribes to agree on some common political principle in the abstract is a difficult task (see Lawrence of Arabia). The tribes are loyal to whoever ‘rents’ their territory from them. When these ‘renters’ change or are replaced, the tribes drive a bargain with the new ‘renters’. That is why considering the actions of the tribes in Syria is an important part of the analyses of the force arrays.

The Battle for Syrian Oil and Gas

There is a major battle going on for control of the Syrian oil and gas industry among the U.S., the Russians, the Iranians and the Turks. The U.S. operates through the Kurdish forces of the SDF in the region which controls the oil fields in the northeast of the country. It contains 95 percent of all Syrian oil and gas potential, including al-Omar, the country’s largest oil field. Prior to the war, these resources produced some 387,000 barrels of oil per day and 7.8 billion cubic meters of natural gas annually. However, more significantly, nearly all the existing Syrian oil reserves – estimated at around 2.5 billion barrels – are located in the area currently occupied by the Kurds and the SDF.

In addition to Syria’s largest oil field, they also control the Conoco gas plant, the country’s largest. Originally built by U.S. oil and gas giant ConocoPhillips, the plant was operated by Conoco until 2005, after which Bush-era sanctions made it difficult to operate in Syria. Other foreign oil companies, like Shell, also left Syria as a result of the sanctions.

The SDF and the Kurds have an advantage. Not only are they selling oil to Assad, they are able to take the Syrian oil through to Iraqi Kurdistan where it can be refined and sent out through the Ceyhan pipeline to the world markets without sanctions.

Russia

In late January 2019, Russia signed an agreement with Assad and the Syrian Government to take over Syrian oil and gas. Russia will have exclusive rights to produce oil and gas in Syria. The agreement goes significantly beyond that, stipulating the rehabilitation of damaged rigs and infrastructure, energy advisory support, and training a new generation of Syrian oil technicians. This is likely to be a very expensive task— IMF put the estimate expenses at $27 billion in 2015 but the current estimate lies most likely between $35–40 billion. This includes the totality of rigs, pipelines, pumping stations etc. to be repaired and put back into operation.

While Russia has access to the gas fields near Palmyra, its access to the North-eastern oil fields is blocked by the SDF control.

Another impediment to Russia’s takeover of Syrian oil and gas supplies is finding a Russian company which is not itself under sanctions to market the products. U.S. and European sanctions have restrained the free movement and growth of that sector so Russia is more likely to concentrate on the gas sector. Most of Syria’s gas is used by the domestic energy sector and is burned for electrical power. That is a stable domestic market for the gas and, if the implied gas boom offshore Syria is ever allowed to function, offers Russia the possibility of a return on its investment by gas exports through the new pipelines being built in the region.

[(Pyotr Veliky missile cruiser makes port call in Tartus, Syria (Image: Sputnik)]

[(Pyotr Veliky missile cruiser makes port call in Tartus, Syria (Image: Sputnik)]

Iran

Iran has a great deal at stake in Syria and Syrian energy. Until October 2018, Iran had been supplying oil to Syria in tankers. At that point Iran, watchful of its dwindling resources due to sanctions being re-imposed by the U.S., ran out of available funds to keep up with its expanded military presence in Syria. The Revolutionary Guard has thousands of soldiers in Syria supporting Assad and their presence has kept open a secure landline to Hezbollah forces in Lebanon supported by Iran.

Since the stoppage of Iranian tankers to Syria there has been a growing shortage of petroleum products in Syria. Residents of the Syrian capital have been forced to once again use horse-led carriages to get around as a severe fuel crisis has taken hold. The regime’s response to the crisis has been to ration gasoline. Private cars are allowed 20 litres every five days while taxis can receive 20 litres every 48 hours.

The situation has become so desperate the Syrian regime has been buying fuel from a company run by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham rebel group, which controls opposition Idlib province.

Tehran has had to cut $200 million in credit for fuel supplies to Damascus. Syria consumes around 100,000 barrels of oil a day, but only produces around a quarter or this, according to the government, forcing Damascus to import around 2 to 3 million barrels from Iran. This credit line for oil supplies started in October 2013 with Damascus racking up $3 billion in debt so far.

On February 25th, 2019, Syrian president Assad met with Iranian President Hassan Rouhani and Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei in Tehran. They agreed that Iran and Syria would join in a number of commercial deals for which Iran would provide credit. As part of this restatement of their co-operation, the Syrians have focused on Latakia (the Alawi heartland) for a number of military and electrical power projects. Most importantly, Syria has turned over the running of the port of Latakia to Iran; a crucial step towards Iran having a permanent route to Lebanon and the sea to maintain its presence in Syria. Iran has also promised to address Syria’s ongoing fuel shortage by sending all future shipments of heating fuel, cooking fuel, and gasoline to the Iranian-leased section of Latakia, once it is fully operational.

This leasing of Latakia to Iran was seen as a challenge to Russia at its naval base at Tartus and air base at Hmeimim. Having the Iranian presence so close might well obstruct Russian surveillance and intelligence gathering, jam radio-electronic technology, and jeopardize Russian air-defences, aircraft, and the lives of military personnel. The frequent drone attacks on Iranian troops and movements by Israel might attract further interest in the area.

In recent months the Israelis have been attacking Iranian installations within Syria, especially when Iran ships missiles and other equipment to Syria and onwards to Hezbollah. It is a badly-kept secret that Russia, which operates several sophisticated anti-aircraft and anti-missile defence systems in Syria, turns them off before the Israelis strike Iranian targets in Syria after communications with the Israeli ‘hotline’. The Israelis are pleased with this, as are the Russians, in that it is widely believed Israel has developed effective counter-measures to the S-400 anti-aircraft system. A public demonstration of this would embarrass the Russian military and damp down foreign S-400 sales. Having the Iranian military control Latakia port changes many of the strategic programs for the Russian military.

Russia, upset at this move by Syria, made an analogous offer. It was agreed that a Russian firm, Stroytransgaz, would take over Syria’s largest port of Tartus for 49 years and invest $500 million in expanding it. Today, the port of Tartus is too small and shallow to accept the larger vessels used in international commerce. When it is improved and expanded, it can also provide access to the Russian naval fleet. Unspoken in the agreement was that Russian companies would take advantage of the opportunities off Tartus for a possible opening of Syrian offshore gas facilities.

Turkey

The third major player in the search for Syrian oil and gas is Turkey. Turkey has a long and notorious history of intervention inside Syria in pursuit of Syrian oil. The fundamental problem for assessing the Turkish role in the region, however, is the long and well-documented charges of corruption by Turkish President Recep Erdogan.

In December 2015, the Russian Defence Ministry accused Erdogan and his sons of ‘stealing’ Syrian oil which they trucked back to Turkey for sale. The ministry produced extensive photographic evidence of this claim, inviting journalists to see satellite images and video purporting to show tanker trucks with oil crossing into Turkey from ISIS-held territory. It was alleged that Erdogan did so in direct collaboration with ISIS from whom they purchased the oil.

Deputy Defence Minister Anatoly Antonov stated, “According to available information, the highest level of the political leadership of the country, President Erdogan and his family, are involved in this criminal business. They have invaded the territory of another country and are brazenly plundering it.”

The Russian Defence Ministry also alleged that the same criminal networks which were smuggling oil into Turkey were also supplying weapons, equipment and training to ISIS and other Islamist groups. Sergei Rudskoy of the Russian General Staff stated, “According to our reliable intelligence data, Turkey has been carrying out such operations for a long period and on a regular basis. And most importantly, it does not plan to stop them.”

This expose of the Turkish role in supporting ISIS and Al Nusra was the origin of Erdogan’s break with his former partner, Fethullah Gulen. Erdogan was losing support in Turkey with all his foreign policy tergiversations, and the recurrence of corruption charges over his family’s involvement in marketing Daesh oil was threatening in the national assembly.

In January 2015, secret official documents about the searching of three trucks belonging to Turkey’s national intelligence service Mille Istihbarat Teskilati (MIT) were leaked online to the Turkish newspaper Cumhuriyet, once again corroborating suspicions that Ankara has not been playing a clean game in Syria. According to authenticated documents the trucks were found to be transporting missiles, mortars and anti-aircraft ammunition. The Gendarmerie General Command, which authored the reports, alleged, “The trucks were carrying weapons and supplies to the al-Qaeda terror organization.”

Yet, the Turkish public was unable to see these documents because the government immediately obtained a court injunction banning all reporting about the affair. The editor and publisher of Cumhuriyet were jailed for treason. There have been many additional reports of MIT officers acting as paymasters of both ISIS and the Al-Nusra Front in Syria and many more Turkish journalists have been jailed.

Since then, and after the trial and imprisonment of thousands of Turkish military officers, journalists, trades unionists and politicians in the aborted 2016 coup, Erdogan has directed his energies toward obtaining oil and gas supplies from Syria and elsewhere in the Eastern Mediterranean Region.

Theoretically, Turkey is in a strong strategic position vis-à-vis energy markets and suppliers, thanks to the ongoing TurkStream project with Russia, the Transanatolian Pipeline Project (TANAP) with Azerbaijan, and the East Anatolia gas-transmission line with Iraq. Having been thwarted by the exposure of Turkey’s oil theft in Syria, Turkey has had to rely on Russia for its oil and gas supplies. Erdogan’s vision of becoming the oil and gas hub for Europe is not proceeding very well.

Although the share of imported gas originating from Russia has decreased continuously over recent years, it is still more than 50 percent. At around 17 percent, the second-largest share of Turkey’s gas mix has been imported from Iran over the last years. Turkey succeeded in being granted an exemption from U.S. Iranian sanctions, but President Trump recently announced that these waivers have been withdrawn.

Turkey has maintained its hostility to the Kurds, it has invaded Afrin, and it threatens to attack the SDF in Syria in an effort to block Rojava (a united Kurdish state) on its borders. It has also tried to drive Kurdish forces from ‘Deir ez-Zor and other oil and gas producing regions of Northern Syria. Turkey, which initially financed the Turkomen minority participation in the creation of the SDF, has now sent money, arms and supplies through MIT to the Arabian tribes in the SDF areas around the oil installations to foment a rebellion against the Kurds within the SDF. In addition to their military efforts, the Turks have maintained their support for the Al-Nusra front (‘Jabhat al-Nusra’) an erstwhile al-Qaeda affiliate, and several other Salafist forces opposed to Assad as well as opposed to the Kurds.

Presidents Vladimir Putin and Recep Tayyip Erdogan [Image AP]

Presidents Vladimir Putin and Recep Tayyip Erdogan [Image AP]

The Turks have also supported several Arab tribes in the region. Sheikh al-Bashir, leader of the Baggara tribe in Syria’s eastern ‘Deir ez-Zor Governorate and a former member of the Syrian Parliament, has organized several armed groups that have actively sought to attack Kurds in and around the ethnically mixed city of Ras al- ‘Ayn in the north-eastern area of al-Hasakah governance, along the Turkish border. Pro-government Baggara fighters, without links to Sheikh al-Bashir, have also participated in attacks against the Kurdish PYD.

The participation of Baggara tribal fighters in attacks against Kurds demonstrates the continuingly fragile state of Kurdish and Arab tribal relations in ethnically mixed regions such as Aleppo and al-Jazirah. Many of the tribes lost control of the oil wells in their region to Daesh and to Al-Nusra. These oil facilities are now in the hands of the PYD Kurds and the local tribesmen, and Assad wants them back. Turkey is supporting both in the efforts around ‘Deir ez-Zor.

With the Kurdish loss of the oil facilities around Kirkuk by the Iraqi reaction to the Kurdish Referendum, the loss of the ‘Deir ez-Zor facilities would have a major impact on Kurdish economic plans.

Recently, the Arab residents of eastern Syria have complained that the YPG-led SDF administration seems to favour the Kurdish majority areas of northern Syria and has neglected Arab areas, where living conditions are poor and many towns remain without electricity. Not only have the Kurds been taking the oil to Iraqi Kurdistan, they have been shipping increased volumes of the oil and gas to the Assad Government in Damascus to make up for the drop-off in supplies from the sanctioned Iran. The Turks are pushing the line that the Kurds are taking all the money and not sharing properly with the tribes.

The announced Trump policy of speedily withdrawing U.S. forces from Syria has added to the aggravation. The local tribes put their faith in the YPG leadership in forming the SDF because the Kurds brought U.S. might with them into the bargain. As it became clear that the U.S. was withdrawing its overt support for the Kurds and the YPG, their stature was reduced in the SDF coalition and the tribes began looking elsewhere to see who would take their place; preferably someone who would pay them more than the Kurds. Turkey has exacerbated this development, but, at the moment, is increasingly reliant on Russia for additional supplies.

Turkey has also been attempting to muscle-in on the massive gas discoveries off of Cyprus; especially in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus which Turkey, alone, recognizes as a separate state. It has been unsuccessful in its claims despite its frequent statements and petty harassments of the drillers.

Gas Discoveries in the Eastern Mediterranean

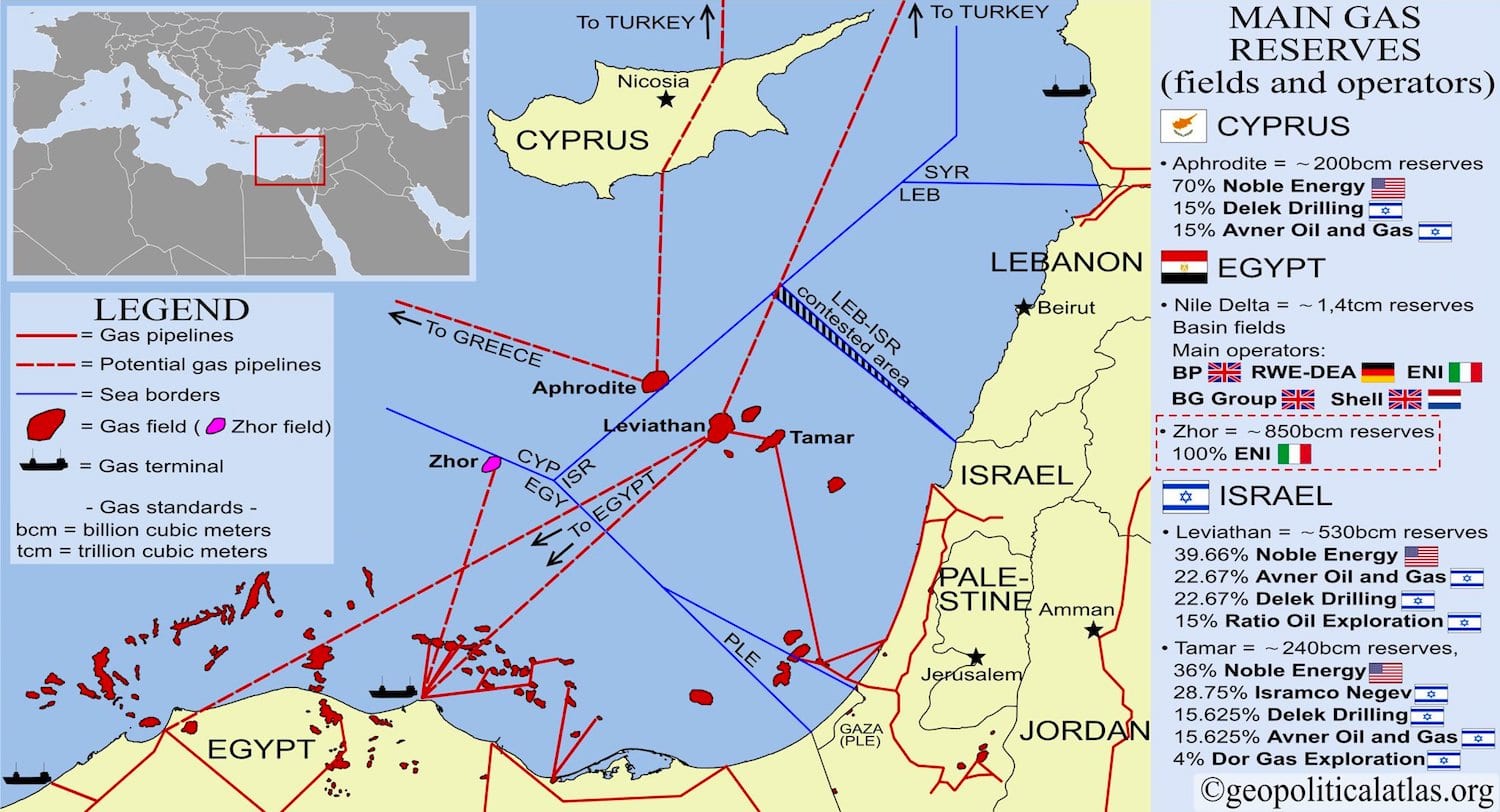

In December 2011, U.S. company Noble Energy announced a successful deep water gas find offshore at Cyprus in a field estimated to hold at least 7 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. This made Cyprus, overnight, a potential major player in the gas to Europe business. Cyprus and Israel agreed to co-operate on building a pipeline from Israel’s offshore facilities to Cyprus and continuing to Europe through joining up with the new offshore Greek gas fields.

The main beneficiary so far of the gas discoveries in the Eastern Mediterranean has been Israel. Some Israeli gas was provided by the Yam Tethys – the Mari B and Noa – natural gas reservoirs discovered in 1999 and 2000 by a partnership of Noble Energy and the Israeli company Delek Energy. These reservoirs marked the start of a new era. Mari-B and Noa established the Israeli offshore holdings in the oil and gas game for the very first time, and introduced natural gas to the Israeli market. Yam Tethys has been supplying natural gas to the Israeli market since 2004. The major clients of Yam Tethys include the IEC (Israeli Electric Corporation); ICL (Israel Chemicals, Ltd.) and the sole Israeli Independent Power Producer.

Then, in 2009, Noble Energy discovered the Tamar field in the Levantine Basin some 50 miles west of Israel’s port of Haifa with an estimated 8.3 tcf (trillion cubic feet) of highest quality natural gas. Tamar was the world’s largest gas discovery in 2009. At the time, the Yam Tethys gas reserves were estimated at only 1.5 tcf. Moreover, estimates were that Yam Tethys, which supplied about 70 per cent of the country’s natural gas, would be depleted within three years.

With Tamar, prospects began to look considerably better. Then, just a year after Tamar, the same consortium led by Noble Energy struck the largest gas find in its decades-long history at Leviathan in the same Levantine geological basin. Present estimates are that the Leviathan field holds at least 17 tcf of gas. In a few months, Israel went from gas famine to feast. There were also large discoveries of oil in the same basin. The USGS, (US Geological Survey), stated that undiscovered oil and gas resources of the Levant Basin Province amount to 1.68 billion barrels of oil, and 122 tcf of gas.

[Main gas fields in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea (via geopoliticalatlas.org)]

[Main gas fields in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea (via geopoliticalatlas.org)]

There have been claims by both Lebanon and Syria that their maritime zones include part of the Tamar and Leviathan fields, but they are in no position to enforce their claims. Although Lebanon believes it has a claim to the Leviathan field, Lebanon and Israel are technically at war and do not recognise either land or sea borders. Israel has declared its maritime boundaries with Lebanon.

Based on its boundaries on land, Israel established a maritime zone that veers well to the north, an area that encompasses all the known major gas fields. Lebanon responded by submitting to the United Nations the coordinates of what it says are its maritime boundaries. It also lodged a formal protest against Israel.

However, Israel, like the U.S., has never ratified the 1982 UN Convention on Law of the Sea dividing world subsea mineral rights. While the Israeli gas wells at Leviathan are within undisputed Israeli territory, Lebanon believes the field extends into their subsea waters. The Lebanese Hezbollah claims that the Tamar gas field, which has just begun gas deliveries, belongs to Lebanon.

Syria was too busy to advance its claims at the time but, in late 2018, Oil and Mineral Resources Minister Ali Ghanem said contracts for five offshore blocks had been signed with “friendly countries”. He also said Syria has an estimated 1,250 billion cubic metres of offshore gas reserves. The report did not say when or how the Syrian government had appraised the reserves.

As Israel’s gas reserves are expanding it is beginning to introduce new technologies to its operation. The Greek energy company, Energean, will produce gas by 2020 from the Karish and Tanin fields using the FPSO method. Egypt, as well, has expanded its offshore gas industry.

The irony of the delay and unlikelihood of Syria’s claim to its offshore gas is that the U.S. has just recognised the legal claim of Israel to the Golan Heights, taken from Syria after their last war. The Golan is the site of Syria’s second biggest, and until now, unexploited, gas field.

Water, Water is Not Everywhere – The Water Crisis

Syria was never a rich state and was vulnerable to two major non-political challenges over the years which it found difficult to address: oil and water. The oil and gas problems have been well understood. The water problem, however, is more complicated.

There is a severe crisis of adequate supplies of fresh water in the region. Turkey’s geographical position as containing the source of both the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers gives it a great advantage in the competition for water. The twin rivers rise in the high mountains of north-eastern Anatolia and flow through Turkey, Syria and Iraq before eventually merging to form the Shatt al-‘Arab, which empties into the Gulf. Turkey is the upstream country and has not traditionally enjoyed warm relations with the Arab countries downstream. Crucially, it controls the water supply of the Euphrates-Tigris River Basin.

Approximately 90 per cent of the water flow in the Euphrates and 50 per cent in the Tigris originate in Turkey. This has left Syria and Iraq vulnerable. The Turks only use about 35% of the water flow and this is largely because it manages the flow through an elaborate system of dams.

In the 1960s, Turkey, Syria and Iraq negotiated a new phase of their relationship over water, as a result of Turkey’s decision to construct the Keban Dam on the Euphrates. After prolonged negotiations, Turkey guaranteed to maintain a discharge of 350 m3/s immediately downstream from the dam, provided that the natural flow of the river was adequate to supply this discharge. This was communicated to Syria and Iraq the same year. During this meeting Turkey proposed the establishment of a Joint Technical Committee (JTC) which would inspect each river to determine its average yearly discharge.

In 1965, the three nations met again to exchange technical data on the Haditha (Iraq), Tabqa (Syria) and Keban (Turkey) dams being built on the Euphrates. There were several small procedural agreements over the next few years but there was no overall agreement on the ownership and use of the water. In 1987 the Turks and the Syrians made an interim protocol on the waters of the Euphrates as Turkey was filling its Ataturk dam. Since 1975, Turkey’s extensive dam and hydropower construction has reportedly reduced water flows into Iraq and Syria by approximately 80 per cent and 40 per cent respectively.

[The Syrian drought caused 75 percent of Syria’s farms to fail and 85 percent of livestock to die between 2006 and 2011, according to the United Nations.]

[The Syrian drought caused 75 percent of Syria’s farms to fail and 85 percent of livestock to die between 2006 and 2011, according to the United Nations.]

The pièce de résistance of the program of dam-building in Turkey was the gigantic Southern Anatolian Project (known by its Turkish acronym, GAP), which commenced in the 1970s and encompasses 22 dams, 19 hydroelectric power plants and several irrigation networks. GAP remains the second biggest integrated water development project in the world, covering approximately 10 percent of Turkey’s population and an equivalent surface area.

Nonetheless, there is and remains a critical shortage of water in the region. It was the continuing crisis over water which provided the backdrop to the Syrian Civil War. The drought during 2005 caused 75 percent of Syria’s farms to fail and 85 percent of livestock to die between 2006 and 2011, according to the United Nations.

By 2011, drought-related crop failure in Syria had pushed up to 1.5 million displaced farmers to abandon their land. The displaced became a wellspring of recruits for the Free Syrian Army and for such groups as the Islamic State (Daesh) and al Qaeda. Drought, and the lack of governmental remediation was a central motivating factor in the anti-government rebellion in Syria.

Moreover, a 2011 study shows that the rebel strongholds of Aleppo, ‘Deir ez-Azor, and Raqqa were among the areas hardest hit by crop failure. Drought changed the economic, social, and political landscape of Syria and was a prime motivator for the disillusion of the Arab tribes with the Syrian Government which was not living up to its bargain to supply them with water and energy.

There is still a massive deficit of water in the region as climate change accelerates. The Turkish “red line” of prohibiting the Kurdish troops in Northern Syria controlling both sides of the Euphrates was generated by Turkish fears of giving the Kurds control of the water supplies of the Euphrates into central and southern Syria.

The important dimension of this struggle for water is that, while Turkey controls the water supply of the Tigris and Euphrates, the rivers rise and flow through that part of Turkey which is the homeland of the Kurds. As the struggle between Erdogan and the Kurds continues there is little real ability of the Turks inside Turkey to prevent actions by the Kurds in their own mountains from diminishing further the flows of water which will have a devastating effect on the downstream nations.

It’s better to fix what you have, than wait to get what you don’t have

The problems facing Syria over asserting full control over the whole of Syria are enormous, prompting a response which might allow for the partition of the country. To a large extent this doesn’t depend on the Syrians alone; the Russians, Iranians, Turks, Kurds and the U.S. will all have a say.

At the heart of that decision will be the question of security, the end of terrorism and the more fundamental problems of oil and water. As long as the U.S. presses its demands on Iran and interdicts its exports, the concurrent pressures on Syria, Hezbollah and Hamas will not be resolved. The dispatch of two US Navy carrier groups to the Eastern Mediterranean will make it much more expensive for Russia to compete for influence in the region as it doesn’t have the comparable equipment. The key factor will be Turkey.

The Turkish military may have been beheaded by Erdogan with many leaders jailed, but the recent elections could be an indication that the political tide may be changing and that the failure of Erdogan to deliver a stable economy may seal his fate. Erdogan has little room in which to manoeuvre and there is a rising interest in changing the restrictions of the Treaty of Montreux which gives Turkey control of naval access to the Black Sea. Turkey’s place in NATO also appears weak and fragile as Erdogan insists on buying Russian military radar for use in a co-ordinated NATO belt of security in the region.

Nothing seems likely to change much in the region but the financial pressures and sanctions on Russia, Iran and Syria will continue to constrain the willingness to expand the search by Lebanon and Syria for offshore gas. The Israelis have used their new supplies of energy to construct elaborate systems of desalinisation, thus removing the water question from their equation. The gift of Golan gas and oil to Israel is a blow to Syria and a boon to Israel.

As the old Arab proverb indicates, it is time to stop destroying Syria and get on with fixing it. إصلاح الموجود خير من انتظار المفقود (“It’s better to fix what you have than wait to get what you don’t have”).

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Dr. Gary K. Busch, for LIMA CHARLIE WORLD

[Edited by John Sjoholm and Anthony A. LoPresti]